Behaviour support and restrictive practices are some of the most highly regulated parts of the NDIS. Anyone involved in the delivery of this support – from the providers and individual practitioners recommending behaviour support to the providers implementing restrictive practices – must be registered with the NDIS Quality and Safeguards Commission (the Commission). In addition, all Behaviour Support Plans containing restrictive practices must go through a rigorous authorisation process (via local state and territory agencies), then be lodged with the NDIS Commission, and reviewed at least once every 12 months. With the recent release of the Commission’s Annual Report 2020–2021 showing significant use of unauthorised restrictive practices (URPs), we have taken a deeper look and posed a simple but crucial question: “What is going on?”

Reportable incidents

We know that the most important role of the Commission is to keep people with a disability safe – including by establishing frameworks to make sure only high-quality providers are in the game, investigating complaints, and having mechanisms in place to identify and respond when the things that shouldn’t happen unfortunately do.

The Annual Report tells us that in 2020–2021, NDIS providers notified the Commission of 1,044,851 reportable incidents. These included alleged sexual misconduct, death, alleged unlawful physical or sexual conduct, serious injury, alleged abuse and neglect, and the unauthorised use of a restrictive practice.

The role of the Commission when considering reportable incidents includes:

- Overseeing the management of reportable incidents by registered NDIS providers and, where incidents identify potential or actual breaches of the Code of Conduct, investigating and managing any requisite action

- Requiring providers to take a variety of actions to respond to an incident, if the Commission is not satisfied that appropriate actions have already been taken

- Referring matters to other relevant authorities when appropriate

- Reviewing and sharing reportable incident data to identify systemic issues to be addressed and driving improvement actions through registered NDIS provider reporting on reportable incidents and compliance activity.

The Commission also acts on incidents requiring a regulatory response.

Unauthorised use of restrictive practices

Of the 1,044,851 reportable incidents lodged by NDIS providers in 2020–2021, a whopping 98.7%, (or 1,032,064) concerned the use of URPs. That is a staggeringly high number no matter how you look at it. It’s surely not possible for even the most well-resourced organisation to review and consider each one of these incidents. We know the Commission is not that well resourced, so why is it collecting this information if it doesn’t have the capacity to review each reportable incident? The Annual Report says quite clearly that “the inclusion of unauthorised use of restrictive practices as a reportable incident is designed to drive compliance by registered NDIS providers to have a Behaviour Support Plan in place and seek to have restrictive practices authorised”.

So, is it fair to assume that implementing providers, a million times over (quite literally), are choosing not to comply with the requirement to have a Behaviour Support Plan in place and restrictive practices authorised, or is something else going on?

Authorisation for restrictive practices

While the process for authorising the use of restrictive practices varies across the states and territories, a consistent requirement is that a Behaviour Support Plan containing the use of a restrictive practice must be developed by a registered Behaviour Support Practitioner. This plan is then used by the registered implementing provider to seek authorisation from its state or territory before the plan is lodged with the Commission.

Each Behaviour Support Plan containing a restrictive practice must be reviewed at least once every 12 months. If a Behaviour Support Plan is not reviewed within this timeframe and a new authorisation is sought, the use of these restrictive practices (if they continue) becomes unauthorised. To be clear, in many instances – such as medication to support a person’s anxiety or locking the front door to stop someone from wandering to the railway station – it would be dangerous to stop a practice without proper review and planning simply because a plan has expired.

Behaviour Support Practitioners

On 30 June 2021, there were 6,686 Behaviour Support Practitioners registered with the Commission. It’s worth recalling that Behaviour Support Practitioners must work for a registered Behaviour Support Provider and must be individually registered to be able to develop a Behaviour Support Plan that recommends the use of any restrictive practice.

In the 2020–2021 reporting period, 10,109 Behaviour Support Plans containing restrictive practices were lodged with the Commission. In 2019–2020, 3,745 registered Behaviour Support Practitioners delivered 6,074 Behaviour Support Plans.

On the face of it, this looks like Behaviour Support Practitioners are averaging fewer than two Behaviour Support Plans in each of the last two years, but we know that these numbers simply don’t add up.

Any discussion with participants and families, providers implementing restrictive practices, and Behaviour Support Practitioners themselves will tell you that the demand for services far exceeds supply. In many jurisdictions, wait list times can exceed six to eight months, and in others, Behaviour Support Providers have “closed their books”.

While it is difficult to find data on the number of registered Behaviour Support Practitioners as opposed to active Behaviour Support Practitioners, the data does tell us that across many provider groups, not all providers that are registered are actively providing services.

The Commission’s process to assess the suitability of Behaviour Support Practitioners (rolling out across the country in 2021 and 2022) is likely to reduce that number even further, as many Behaviour Support Practitioners either opt out or are found to be lacking in the necessary skills and experience.

While there has been investment in training and upskilling Behaviour Support Practitioners through a range of initiatives including BSP Capability Building Grants, the Thin Markets project, and the Building the Local Care Workforce Initiative, demand remains excessively high.

A million reasons why

We need to be very clear here – the use of restrictive practices without authorisation and proper oversight is a violation of a person’s human rights and can lead to significant harm and long-term trauma. The framework established by the Commission is absolutely required to ensure not only oversight of the use of restrictive practices, but also to ensure they occur alongside strategies targeted towards reduction and elimination of their use.

The simple reality, however facing many participants, families, and implementing providers is that it is often impossible to find a Behaviour Support Practitioner to review and recommended the use of restrictive practices in a timely way. Therefore, plans are expiring without review, and the continued use of restrictive practices becomes a reportable incident.

Based on the current reporting framework, where there is no ability to differentiate between those practices that have previously been authorised but expired, from those restrictive practices being used for the first time (likely in response to a significant crisis) is it reasonable then to view the significant number of URPs as a compliance issue? Or - is it worth consider if a more nuanced approach to collecting the data on URPs could actually support the Commission’s stated objective to “drive compliance by registered NDIS providers to have a behaviour support plan in place and seek to have restrictive practices authorised”?

When everything is urgent, nothing is urgent

We’ve all heard the “management speak” that when everything is urgent, nothing is urgent, but in this case, it seems hard to argue the point. When you group a million of anything together without the ability to differentiate, making any meaning becomes all but impossible.

Restructuring the way that information is collected about the unauthorised use of restrictive practices and creating the ability to differentiate could lead to vast amounts of meaning being derived from these reportable incidents.

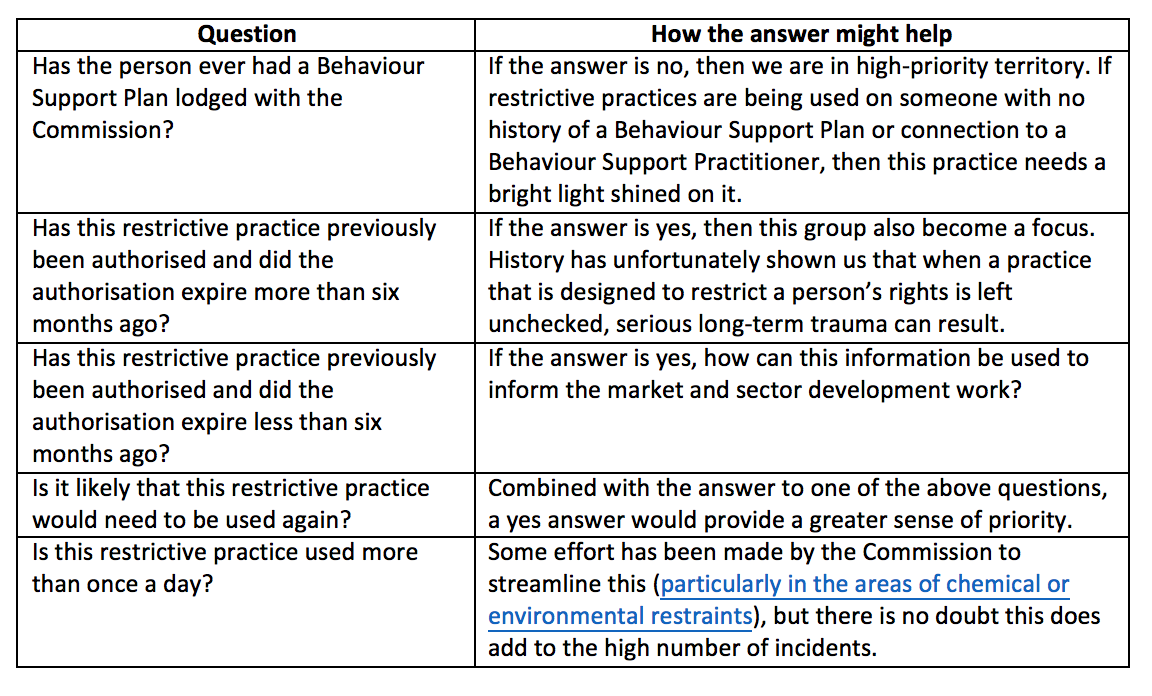

As part of the reportable incidents process for URPs, the additional information in the table below could make a real difference.

The legislative requirement to report on the unauthorised use of restrictive practices as a reportable incident is accepted and necessary to ensure the safety of anyone subject to restrictive practices. Gathering additional data alongside the reportable incident information, however, could enable real analysis of the issues driving these reporting figures to support better outcomes for participants, better data to drive sector development, and ultimately meet the Commission’s goal of improved compliance.

And on a final note…

We need to remember that compliance does not always equal quality. It is important to ensure that Behaviour Support Plans are kept up to date and that the oversight, monitoring, and review of restrictive practices happen in a planned and timely way. Greater importance, however, needs to be placed on the quality of each Behaviour Support Plan, the effectiveness of which can only truly be measured by improvements in a person’s quality of life.

:format(jpg))