People with disability are twice more likely to experience violence than people without disability, with 65% of people with disability experiencing violence after turning 15 (Centre of Research Excellence in Disability and Health). Statistically, that’s about two-thirds of your participants who have experienced violence.

If you work with people with disability, it’s almost certain that you work with people who are experiencing violence. But folks experiencing violence often feel deep-seated shame, so it can be a hidden issue.

There are significantly higher barriers to accessing family violence support for people with disability than for people without disability, so sometimes people simply choose not to, or feel unable to get support.

Here’s what you need to know in order to recognise the signs and respond effectively.

What is family violence?

Family violence, sometimes referred to as domestic violence, is where a person or group of people in a family (or a family-like relationship) exercise power and control over another person, and make that person feel afraid and unsafe. It is different to a couple’s dispute or violence by strangers in the community.

Family violence is usually part of a pattern of behaviour that involves multiple tactics (types of violence) to gain power, control and intimidate. Family violence is not exclusive to intimate partner relationships: for example, children can use violence against their parents, and parents against their children. In some jurisdictions, like Victoria, support workers can be considered ‘family-like’ in the legislation and thus, support workers can also be legally viewed as perpetrators of family violence against the people they support.

While this article focuses on family violence, people with disability are also disproportionately impacted by other forms of violence, as was extensively outlined in the Disability Royal Commission’s Final Report.

Here’s what to look out for

Signs to look out for

A person experiencing violence might be:

- afraid

- anxious to please

- withdrawn

- not making their own choices

- isolated from their support networks and not seeing friends or family

- in a changed state or mood

- suffering injuries

- worried that their partner is following them or knows where they are

- cancelling or not attending their regular appointments

This list isn’t exhaustive - we know there’s lots of ways people experiencing violence may show up that include the above, or none of the above.

Learn the different types of violence

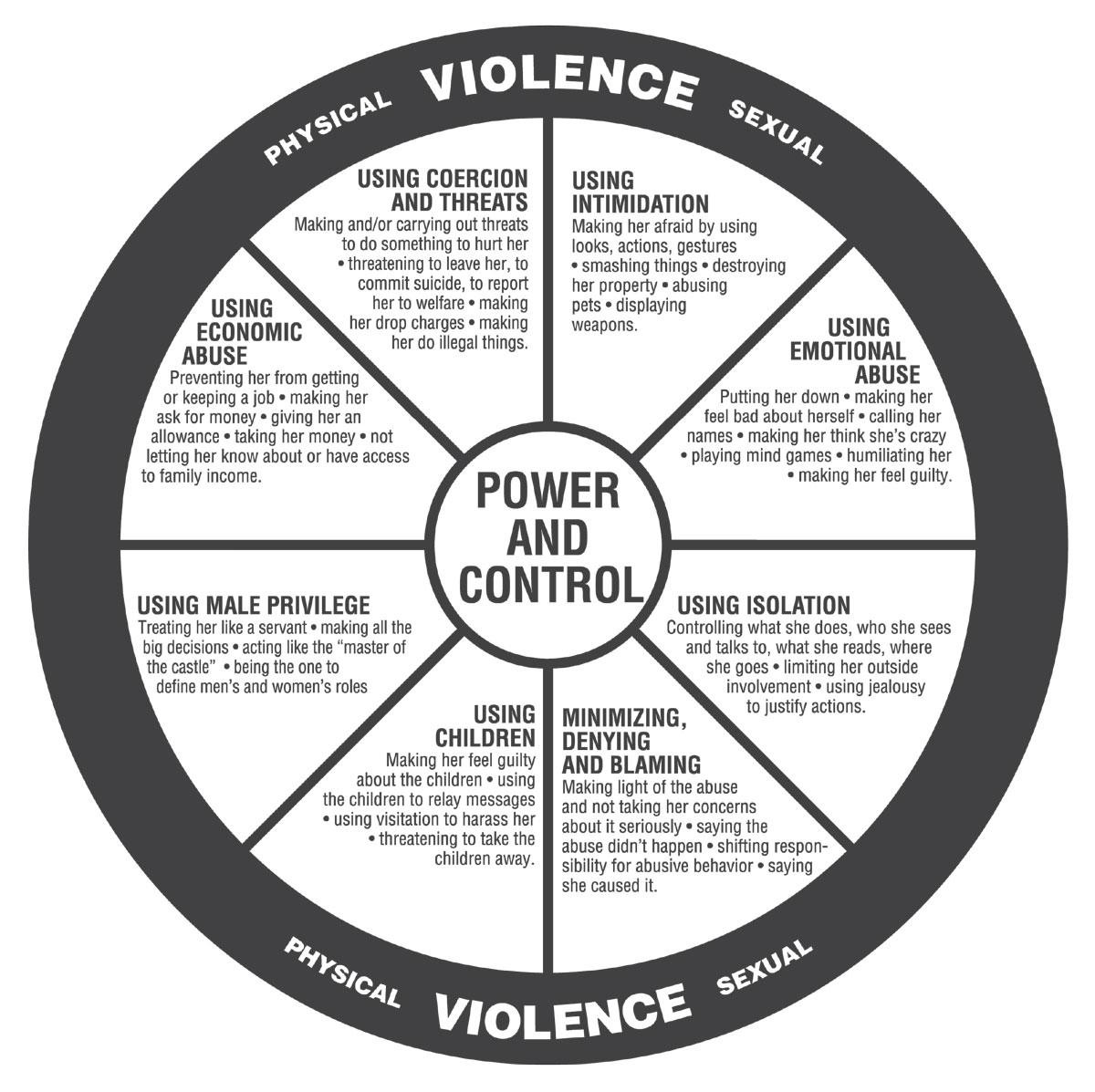

There are different types of family violence, and people rarely experience one in isolation.

Understanding the different types makes us better equipped to identify violence and to help the people we work with identify it as well.

The Duluth Power & Control Wheel is a helpful tool that describes some types of violence and how people use it.

Disability-related abuse

People with disability-specific care needs, may have their care and support needs denied by family or others. Disability-related violence and abuse might look like:

- withholding or refusing care or equipment

- refusing to let care providers into the house

- misusing restrictive practices or medication in a way designed to control someone

- making decisions for someone who has decision-making capacity as a means of exercising power and control and instilling fear.

Intersectional drivers

Some groups are more likely to experience violence. A person’s age, race, identity as a First Nations person, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) background might also increase their risk of violence.

Intersectionality is when a person belongs to more than one of these groups. For example, being a person with disability and being a woman is one of these intersections.

The increased possibility of experiencing violence isn’t a personal shortcoming, it’s because systems are not set up to support intersectionality, which creates vulnerabilities for people. (Think social model of disability: It’s the stairs that are disabling). An example is family violence services aren’t necessarily well resourced to service people with disability or may not have this specialist skills. People who use violence can exploit these vulnerabilities to enable abuse and control.

This diagram shows the intersecting drivers of violence against women and girls with disability, gender inequality and ableism (Women with Disabilities Victoria and Our Watch: Changing The Landscape).

Lack of rights (or: it’s happened before)

The Disability Royal Commission found that violence thrives when people have reduced rights, choice and autonomy.

Closed environments like Supported independent living (SIL) and group homes can become sites for violence. As can situations where a family member is managing a person’s NDIS plans and money.

(Of course, this isn’t always the case, but it’s important to interrogate these situations more carefully - particularly if you see any signs of the abovementioned signs of violence or if you have a feeling something isn’t right.)

What can I do if I suspect someone is experiencing violence?

- Ask them. The Are You Safe At Home? website is a great resource with some strategies to ask people if they’re safe or experiencing violence.

- Listen to them without judgement, and offer to revisit the conversation if needed.

- Believe them. Whatever they say, believe them.

- Affirm them. If someone is experiencing violence, affirm that it is not their fault, they haven’t done anything wrong, the person using violence is accountable for their behaviour, and their harmful behaviour is not ok, and they can get support.

- Refer them to one of the services below that provides a specialised family violence response.

It is particularly vital to believe and affirm people with disability, who too often are not believed and may have previous life experiences that normalise violence.

Your obligations around violence

Providers have legal obligations to take steps if they suspect or know of someone experiencing violence. These include;

NDIS Practice Standards: Core Module 1 Rights and responsibilities: Violence, abuse, neglect, exploitation and discrimination

- The Practice Standards (Core Module) require us to prevent violence. This includes exploitation or neglect perpetrated by services and support workers (including your own organisation), but also requires you to act if you know about, or suspect, other forms of violence.

The NDIS Code of Conduct

Applies to all providers. It requires providers to:

- promptly take steps to raise and act on concerns about matters that might have an impact on the quality and safety of supports provided to people with disability.

- take all reasonable steps to prevent and respond to all forms of violence against, exploitation, neglect, and abuse of people with disability.

- take all reasonable steps to prevent and respond to sexual misconduct.

Legislative obligations

Obligations around family violence are mentioned in:

- The Disability Discrimination Act.

- The Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, explicitly in Article 16.

- In some states and territories, the legislative definition of family or domestic violence can include paid support workers - so you could have additional legislative responsibilities if staff are using violence or unauthorised restrictive practices.

Human rights

- Aside from legislative and compliance requirements, this is a human rights issue. Violence impacts people’s whole lives and greatly reduces their rights.

Where to go for more?

Each state and territory has their own funding for family, domestic and sexual violence services. In Victoria, you will find your local sexual assault service through the Sexual Assault Services Victoria Map. Google will help you find sexual assault services (often called a Centre Against Sexual Assault (CASA) or a Sexual Assault Resource Centre (SARC)) and family violence services near you. Here are some helpful national resources:

National Helplines:

Apps

If you’re in Victoria, you can reach out to me for the Barwon region (email: [email protected]), or our other FVDPLs (website: The Family Violence and Disability Practice Leader initiative (FVDPLI).

The rate of violence experienced by people with disability is staggering. We had a whole Royal Commission into it for Pete’s sake.

Being an active player in preventing and responding when you see or suspect that people are experiencing violence can save lives.

Specialist services have their role, but people with disability don’t always present to specialist services, and sometimes don’t identify their experience as violence.

You can play a pivotal role in helping people take the first step.

By elevating people’s voices, respecting their choice and agency, and listening to them, we can help people to live a life free of violence and abuse. Many folks who have experienced violence go on to live full lives that are not defined by fear or violence, have healthy relationships, and are often exceptional advocates.

:format(jpg))